Every day at school, the bell rings at 12:30. Students don aprons, masks, and hairnets. I try not to get caught swimming upstream as they all file down the hall. Adolescents hustle up the stairs bearing piping hot metal containers – what do they hold? You’ll have to consult the lunch schedule handily posted in every classroom.

Here in the staffroom, if I don’t have a 4th period class, I help the staff dole out lunch. Yes, the staff gets school lunch – a major perk of the job. Trays in white, green, and pink line the designated lunch counter. On each tray: a rectangular plate divided in half, two bowls, chopsticks, and a milk box (like a juice box but with milk, if that wasn’t obvious). One bowl is always filled with rice. The other bowl is usually a soup or stew. Half of your plate is some sort of salad or vegetables, and the other half is either a protein or starch. That’s the formula devised by a food and nutrition teacher in accordance with national standards. Teachers dish it out, and I help put bowls and plates on trays, and trays on desks. Usually, after the food has been dished out, they will even out the portion sizes by redistributing some food from larger servings to augment skimpier servings. In the classroom, kids serve each other.

School lunches in Japan originated during the Meiji Restoration (see how we keep revisiting the Meiji Restoration as we discuss Japan?) The National Institute of Nutrition was founded in Tokyo in 1920, and the first dietitian school in the world followed a few years later. School lunches were suspended during World War II, but were instrumental shortly after the war in addressing rampant malnutrition. The School Lunch Act of 1954 resulted in the vast majority of all schools providing lunch for their students (95% of schools overall, with the number declining slightly after elementary school).

Fun fact: as my Japanese food professor in Singapore relayed to us, whale meat was a staple of school lunches until the 1970s because it was cheap and filling.

As Western fast food and conbinis became popular, the Japanese government enshrined shokuki – or food education – into the school curriculum to promote healthy eating habits. School lunches also feature local ingredients, as 56% of food purchases made by schools in a 2021 study were local. In the words of the Basic Act on Shokuki (2005), food education is “the basis of a human life which is fundamental to intellectual education, moral education, and physical education.” School lunch is such a cultural hallmark that there are school lunch-themed restaurants for the general public and even a School Lunch History Museum in Saitama.

The students are required to eat everything in front of them, to root out picky eaters from society (in some extreme outlying cases, students were force-fed, drawing accusations of human rights violations). The students serve their classmates in the classroom, and everyone cleans up afterwards. This whole system is in stark contrast to the American system. Yes, we also have school lunch, but it’s very different. For one thing, the cost of school lunch in America is nearly double (the average is $61.8 per month, nationally). Even with subsidies to help lower-income families, 55% of schools have unpaid student meal debt, and 87% of districts reported an annual increase in the number of students who cannot afford lunch. As of this January, all students living in the Tokyo area get free lunch. The quality of school lunch in America is also much worse, thanks to our bare-minimum federal standards. This is partially a product of trying to keep the costs of school lunch down – infamously, Ronald Reagan tried to count ketchup as a vegetable. As much as kids complained that Michelle Obama ruined school lunch, her initiative-led changes improved the nutritional quality of lunches, improvements that have since been rolled back. My memory of observing school lunch in high school is that it looked basically like Domino’s.

Enough already – what have you actually been eating! You cry as you shake your fist at your screen, no doubt bored to tears. Well, dear reader, every day has been different. But I’ll outline the past week or so of school lunches.

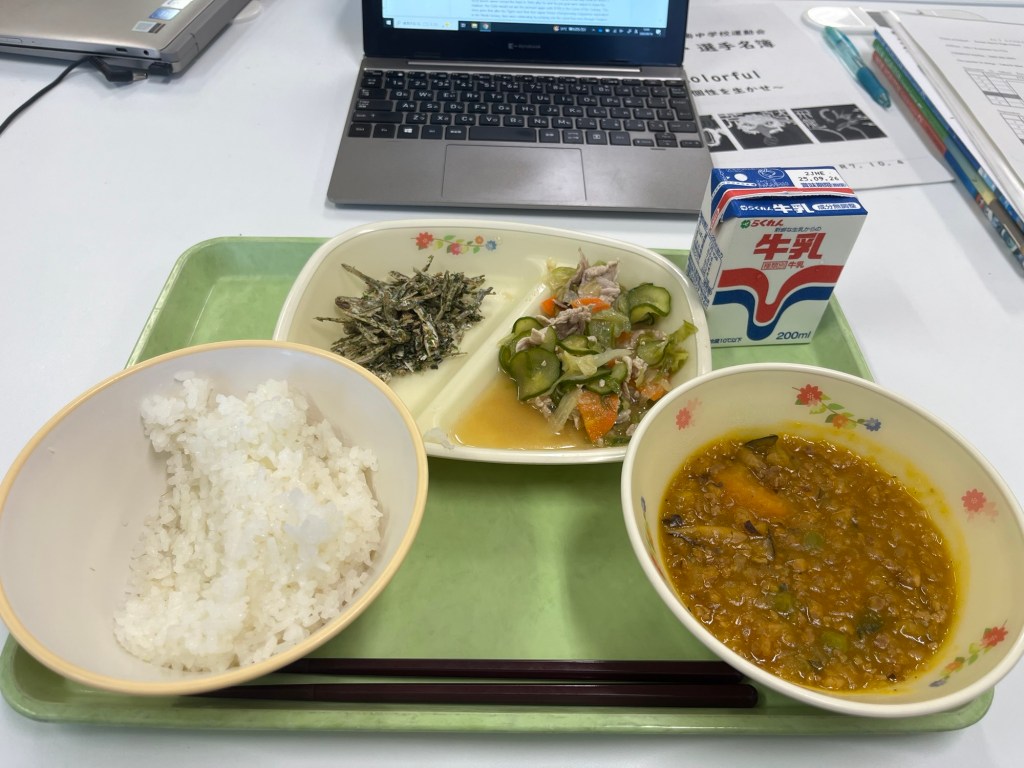

Tuesday, September 16th

- Rice

- Soup: pumpkin and ground meat

- Salad: cucumber, carrot, cabbage, thinly-sliced meat

- Iriko

This was a delicious and hearty soup. I would love a bowl of it on a cold winters’ night. The salad was tasty as well. These small dried fish are iriko, or Japanese sardines. They are really dry and crunchy, they taste more like seaweed than fish. Sometimes they get caught in my throat. On the strength of the soup, this lunch scores high. Grade: A-

Wednesday, September 17th

- Rice

- Furekake: beef

- Unidentified fried thingies

- Salad: cucumber and ?

- Soup: mushroom

- Juice box!

For the life of me, I could not identify these fried nuggets. At first I thought they were karaage, but I actually am not even sure it was meat from an animal. Some parts of them were crunchy in a nut-like fashion. Also, they were lukewarm and soggy to boot. The salad had that reoccuring strange bitter flavor that has cropped up a few times. The soup was simple but fairly hearty. The most exciting part was the juice box.

Remember how Ehime Prefecture is famous for mikan, or mandarin oranges? Here’s some juice that was pretty good. I don’t drink the milk – it goes in the fridge every day – so to get a beverage I wanted to drink was thrilling. This is the only juice thus far though, so it’s a rare occasion. Grade: C+

Thursday, September 18th

- Bread

- Chili con carne

- Salad: fruit with jelly

- Soup: veggies, vermicelli, and wide flat noodles

I think out of a month’s worth of lunches I’ve gotten bread like two or three times. I think I prefer the rice, which as you can see I spruce up with my own furekake from the store (Minecraft-themed). However, I was able to dip my bread into the chili con carne juice. The chili con carne was interesting, and reminded me of a Sloppy Joe without all the tomato. It had a sweet, ketchup-y flavor. I guess this is technically a salad, but really it’s dessert. The soup is good, but nothing to write home about. Grade: B-

Friday, September 19th

- Rice

- Furekake: egg

- Salad: cabbage

- Soup: interesting mix including carrot, quail egg, and squid

- Candied sweet potato with sesame seeds

This was a mid lunch. Not quite filling enough for me, and I had a sesame seed stuck in my teeth for hours. The soup was good, the sweet potato was fine, and the salad was boring. Grade: C

Friday, September 27th

- Kimchi fried rice

- Furekake: N/A

- Soup: Egg drop

- Salad: ham, vermicelli, egg, cucumber with sesame dressing

- Koroke (croquette, like a hash brown)

This was the best lunch I have had yet. The first non-plain rice was very exciting. I would have had more kimchi personally, but still. My koroke were hot and crispy, which is usually not the case with fried foods, and I got two because there were some extras. Soup was warm and tasty, as was my “salad.” Grade: A+

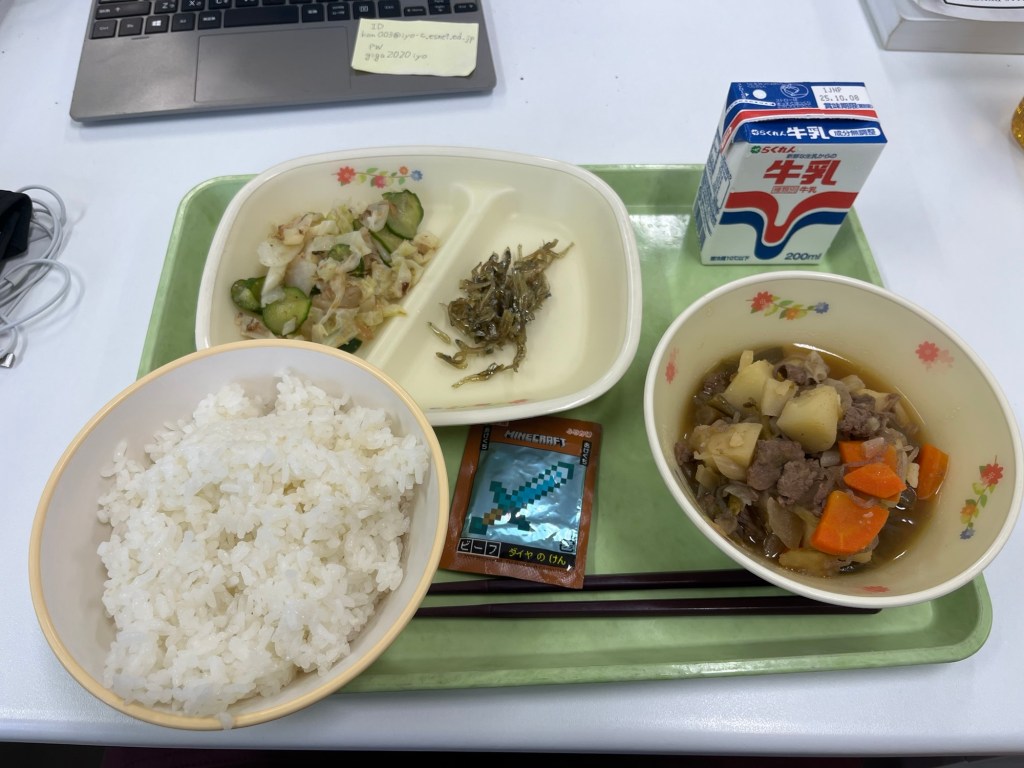

Monday, September 29th

- Rice

- Furekake: beef

- Salad: cucumber, cabbage katsuobushi

- Iriko

- Beef stew with potato, carrot, and onion

This was a very solid lunch. The beef stew was delicious, savory, and slightly sweet from the beef and carrots. Everything was the right texture. I much prefer this style of sweet, glazed iriko, and they are a delicious savory pairing for your rice. They’re divisive among the Iyo ALTs, but I am a big fan. However, the inclusion of katsuobushi – – though I am a big fan of katsuobushi in general – in the salad makes it weirdly bitter. Grade: B+

Overall, school lunch is delicious, and often the highlight of my days. As you can see, it’s also very nutritious, and is a part of education and socialization for the kids.

In the hopes of gaining more insight into the school lunch process, I reached out to a contact provided for me by city hall. Below is a translation of the answers I received to my questions.

Q: Can you give a quick self-introduction? What is your background and how did you end up in this job?

A: My name is Takechi, and I am the director of the Iyo City School Lunch Center. I have worked as an employee of Iyo City Hall for about 30 years, but this is my fourth year as the center’s director. After living alone in the city, I wanted to work in my hometown, where I could have a broader impact on people’s lives, so I joined city hall. I was transferred to my current position four years ago, and I find it rewarding to work with school lunches, one of the most appealing aspects of school life for children and students.

Q: How do you choose the menu for each day?

A: Menu plans are prepared by nutrition teachers dispatched to the city by Ehime Prefecture. The school lunches that students normally eat every day are subject to national nutritional intake standards and hygiene management standards, and menus are prepared while adhering to these standards and taking into consideration the necessary nutritional content, safety, cost, cooking time, etc. School lunches also serve as teaching materials for food education, so they must utilize seasonal ingredients and incorporate menus based on traditional events. The menu plans prepared by the nutrition teachers are finalized after receiving approval from representatives of the school lunch center management committee (two members each from the principal, school lunch director, and PTA members) at a meeting called the Menu Committee. Ingredients are also selected at this meeting, so new menus and ingredients that we would like to use are sometimes selected after hearing a wide range of opinions and tastings.

Q: What is your relationship with local farmers and food producers like? How much of the food served is locally sourced?

A: Food ingredient suppliers are required to register. Those who meet criteria such as location, supply capacity, and creditworthiness are eligible to register and participate in bidding. However, individual farmers previously were not allowed to register as there were large differences in management scale and technology, and they could not be treated equally. However, recently, young farmers and individual farmers who can prove they have been delivering for more than a year are allowed to register. As part of a “food education” class, elementary school students are allowed to use the supplier’s vegetable fields to experience harvesting. The harvested broad beans and corn are then used by students from another school to “husk the broad beans” and “husk the corn”, and the beans and corn are ultimately used as ingredients in school lunches. Also, at the suggestion of a supplier, we had them grow cucumbers in star-shaped molds, and the star-shaped cucumbers were served mixed into school lunches. The percentage of ingredients used that are produced within the prefecture is 69.14% (FY2024 results).

Q: How do you implement shokuiku? Do you work with teachers? Why is it important?

A: School lunches in Japan are provided as part of school education. In order to utilize school lunches as a living teaching material, nutrition teachers are assigned to schools to create menus and are dispatched to school lunch centers where the actual lunches are prepared to provide cooking instruction. As students eat the actual school lunches at school, they gain a deeper understanding of dietary knowledge and appropriate nutritional intake through school lunch instruction from nutrition teachers and school menu broadcasts. In addition, by coming into contact with local agriculture and traditional food culture, they develop the ability to eat thoughtfully. Currently, three nutrition teachers and school nutrition staff work at the school lunch center. The nutrition teachers who practice food education at schools work together with the city and town officials who run the school lunch center, making it possible to provide school lunches and implement food education at the same time.

Q: What are the nutrition guidelines set by the government? How do you make sure they are achieved?

A: The “School Lunch Reference Intakes” are national standards for the amount of food provided per meal at school. (Energy guidelines: elementary school: 650 kcal, junior high school: 830 kcal, etc) When nutrition teachers create menus, they use specialized software to calculate the nutritional content for each elementary and junior high school. After school lunches are served, they also recalculate the amounts actually consumed and check to see how much has actually been achieved, striving to generally meet the national standards.

Q: Japanese school lunch is the envy of the world. How did Japan achieve this, and what advice might you have for other countries with poor school lunch (like my country, America)?

A: Please refer to the following explanation on the Ministry of Agriculture. Forestry and Fisheries’ website (https://www.maff.go.jp//pr/aff/2006/food01.html). The origin of school lunches in Japan is said to be in 1889 (Meiji 22) when a private elementary school called Chuai Elementary School, built within Daitokuji Temple in Tsuruoka Town, Yamagata Prefecture (now Tsuruoka City) provided free lunches to children from struggling families. These lunches were provided with rice and money collected by Daitokuji monks, who visited each household and chanted sutras. Subsequently in 1923 (Taisho 12), school lunches were encouraged by the government as a way to improve children’s nutrition, and gradually became more widespread. However, they were discontinued due to food shortages caused by the war. After the war, food shortages caused children’s nutritional status to deteriorate, and school lunches were reinstated in response to growing public demand. The School Lunch Act was enacted in 1954, legally establishing an implementation system. Article 2 of the act sets out the “Goals of School Lunches.” One of these is “maintaining and promoting health through appropriate nutritional intake,” and school lunches are now prepared with a balanced diet to provide approximately one-third of the daily nutrient needs. When the School Lunch Act was revised and enacted in 2009, its purpose was revised from the perspective of “food education,” and the environment surrounding school lunches has further improved. As for opinions on other countries, we will refrain from commenting, as we recognize that differences in ethnicity and customs, as well as national circumstances, may also play a role!

Q: Do you get to eat school lunch? What was your favorite school lunch meal when you were a student?

A: The director of the school lunch center is the first to taste the prepared school lunch to check for flavor and foreign objects. That’s why I eat school lunch every day. My favorite school lunch as a child was fried bread. “Fried bread” is still a popular menu item served in school lunches today.

Q: How has school lunch changed over the years?

A: After World War II, school lunches consisted of three items bread, milk, and a side dish. However, rice lunches were introduced around 1970, and the menu gradually became more diverse. While the number of side dishes available in bread lunches was limited, a wider range of menus is now available, including Japanese, Western, and Chinese dishes. In recent years, thanks to the ingenuity and efforts of nutritionists and cooks, it has become possible to offer “select school lunches,” where individuals can choose one of two menu options. It is also now possible to provide school lunches that accommodate certain students with food allergies. However, while this diversification is increasing, many issues have also arisen, such as school lunch accidents due to allergies and increased workloads on school staff.

Thanks so much to Takechi from the Iyo City Hall School Lunch Center! I was hoping that they might provide some advice for how to improve America’s school lunch, but I understand not wanting to comment on that in an official capacity. For me, it seems like America’s crappy school lunches are a symptom of the chronic underfunding of our schools that also results in low teacher pay and an unfavorable student-to-teacher ratio.

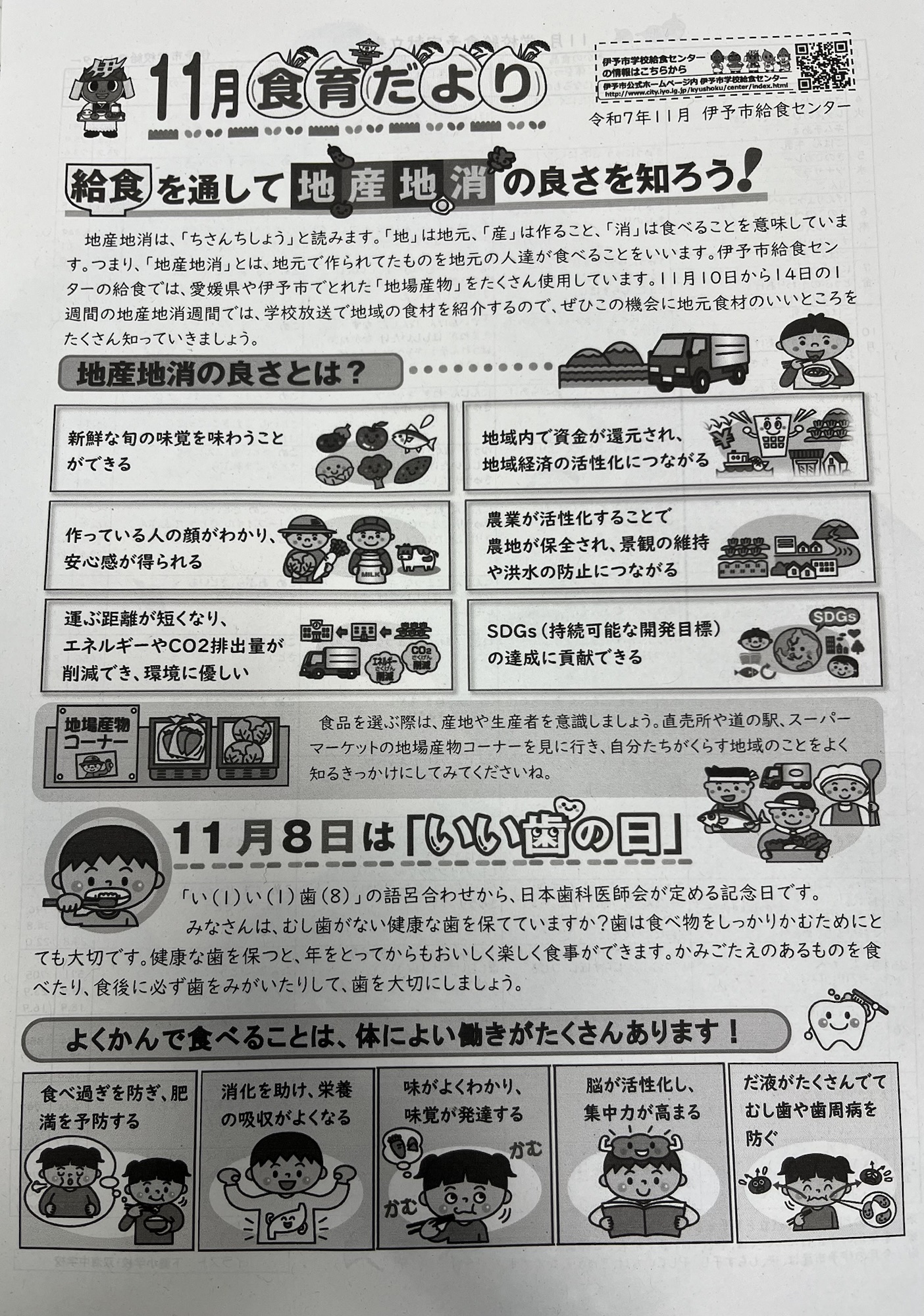

I also got my hands on a handout for November’s shokuiku information. While the translation by Google might be sloppy, it’s still an interesting window into what is valued by the producers and consumers of school lunch.

For more information, you can check out the school lunch section of the Iyo City website here: https://www.city.iyo.lg.jp/kyoiku/kyoiku/kyushoku/index.html

School lunch in Japan seems, like many aspects of society, to be something that an incredible amount of thought and attention is put into – as opposed to its American counterpart, which is a mere afterthought. Can you imagine trying to get a Menu Committee going at your local PTA meeting? The one thing I think that is better about the school lunch experience in America is the communal eating space of the cafeteria. I feel like Japanese kids are missing out on some of the socializing that can be done when everyone eats together – but maybe that’s the point, so they can focus on eating.

PS: I’m having some of my posts cross-posted in the Mikan Blog, my prefecture’s JET-run publication. While this is not very exciting for you, it’s a chance for me to get my writing in front of a slightly larger audience. Check it out if you want to poke around and get some other perspectives on life in Ehime-ken.

– Zev

Leave a reply to Zev Green Cancel reply