Sometime in the last five to ten years, the popularity of Japan and its cultural exports has exploded in the West. I tried to explain this phenomenon to one of my Japanese coworkers: how matcha, manga/anime, and Japanese selvedge denim (something I don’t understand at all) are all the rage amongst fashionable Americans at the moment. No doubt this is correlated with Japan becoming the world’s most popular travel destination. But the canary in the coalmine moment for this incredible popularity of Japanese culture in America, for me, actually came from an unexpected source: Alfredo 2 (2025) by Freddie Gibbs and the Alchemist. Bear with me.

Alfredo 2 is the sequel to Alfredo (2020), the Grammy-nominated hip-hop album put forth by the same tandem. It’s one of my favorite hip-hop albums by two of my favorite contemporary artists. Freddie Gibbs hails from Gary, Indiana, and is arguably the best lyricist in the rap game, capable of complex and creative writing, lyrical content that can make you laugh or make the hair on the back of your neck stand up, and flows and ad-libs that get stuck in your head. He has also worked with legendary producer Madlib on the albums Pinata (2014) and Bandana (2019). The Alchemist, like Madlib, is an eclectic sample-heavy producer who plucks from everything from 70s jazz fusion to world music to niche YouTube videos. He got his start in the 90s with Cypress Hill, but quickly worked his way up to producing for some of the biggest names in the business like Mobb Deep, Nas, and Jadakiss. In the mid-2000s, he was Eminem’s concert DJ, but from the 2010s to the present, he has evolved into arguably the most sought-after producer in underground hip-hop (editor’s note: “underground hip-hop” is the term used by Wikipedia. I think getting nominated for Grammys precludes you from the underground, but a better term to describe rappers who exist slightly below the mainstream, yet are regarded as more skilled MCs than many of their more commercially successful contemporaries, escapes me – alternative?). Some of his finest work is with members of Griselda (Westside Gunn, Conway the Machine, Benny the Butcher), members of Odd Future like Earl Sweatshirt and Domo Genesis, and the likes of Boldy James, Roc Marciano, and Action Bronson (some of my favorites). If all of those names escape you and make you feel really old, the Alchemist also produced the devastating “Meet the Grahams,” one of the many Kendrick Lamar diss tracks against Drake. You should at least be aware of that considering it was discussed at length in mainstream media outlets like the New York Times and resulted in Kendrick Lamar performing at the Super Bowl halftime show.

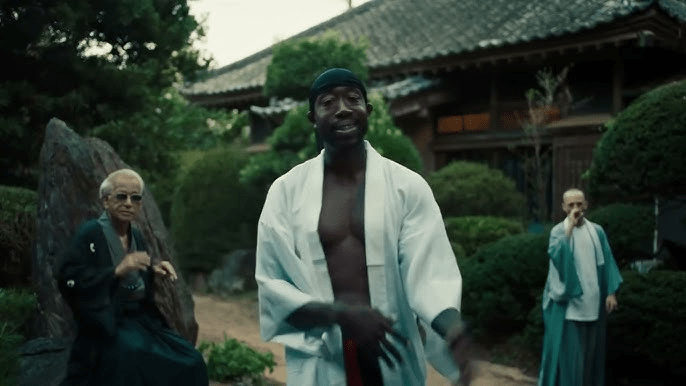

What does this have to do with Japan? Let’s get back on track. The name “Alfredo” is a portmanteau of “Alchemist” and “Freddie” (get it… Al…Fred?) Naturally, the album cover depicts art of a hand puppeteering a dish of fettuccini alfredo. But Alfredo 2‘s cover art has the same hand puppeteering a bowl of… ramen? Samples from Japanese movies serve as intros and outros to songs on the album. Much of the merchandise for the album and accompanying tour has Japanese writing and imagery. There’s even a 15-minute short film set in Japan in which Freddie Gibbs and the Alchemist operate a ramen shop as a front for the yakuza. This fits with Gibbs’s raps about being a cocaine kingpin (one of hip-hop’s most well-trod themes). But why are Freddie Gibbs and the Alchemist obsessed with Japan all of a sudden? In my opinion, this is an example of the larger trend of the surge in popularity of Japanese culture in the West. To properly understand how we got here, we have to go back, way, back to the origins of how Western culture influenced Japan.

We cannot begin without first covering the Meiji Restoration (1868). It’s hard to overstate how dramatic an event this was in Japan’s history. Japan evolved from a feudal state ruled by the Tokugawa Shogunate (military government, 1603-1868) that closed itself off to the outside world to a centralized state ruled by the Emperor that sought to refashion itself in the vein of industrialized Western nations. This had wide-reaching ripples throughout Japanese society. For instance, in my Japanese food class that I took in Singapore, we discussed how the Meiji Restoration changed Japanese cuisine. For more than a thousand years, Japan was essentially a vegetarian nation. But during the Meiji Restoration, the Emperor encouraged the adoption of a more Western-style diet, including the consumption of meat and dairy, as well as the development of Western-style alcohols like beer and whiskey. Beyond food, Japan attempted to modernize by Westernizing in all walks of life. During this time, Japan brought in hundreds of Western oyatoi, foreigners hired by the Japanese government to provide their expertise in respective fields and assist with the Meiji modernization process. This group included diplomats, scientists, scholars, engineers, and even artists. Thus began, arguably, a Japanese fascination with all things Western. For instance;

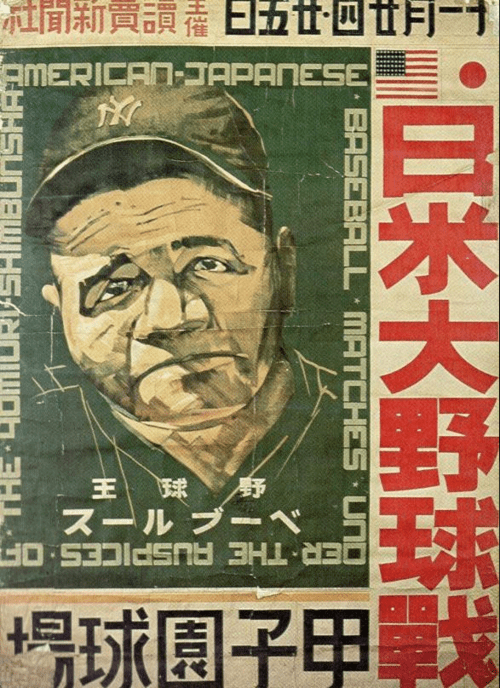

Baseball is the most popular sport in Japan by a wide margin, while in America, it has declined from its peak popularity in the 1950s. Baseball was introduced in Japan during the 1870s by an oyatoi, the American missionary Horace Wilson, who was teaching at Kaisei Academy in Tokyo. The poster on the left advertises the 1934 barnstorming tour of Japan by American baseball stars, including Babe Ruth, which helped to cement Japanese professional baseball as an institution.

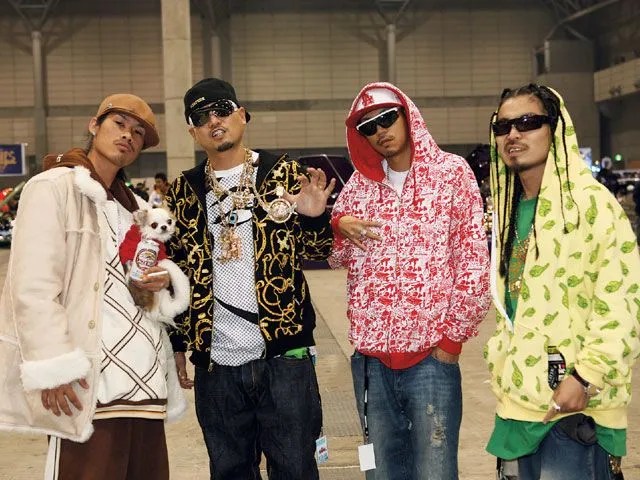

So, yeah. It would be an understatement to say that Japanese society is infatuated with America. Of course, a lot of that is owed to America’s colonization and makeover of Japan following the end of World War II. But Japanese people love everything from mayonnaise to the Rolling Stones. When traversing the far corners of the Internet, you can find a Japanese community centered around any American subculture, from cholos to rockabillies.

Initially, America was just as fascinated with Japanese culture as Japan was with American culture. I came across this great Substack, “An Eccentric Culinary History” by H.D. Miller, in my research, and this is more akin to a proper academic piece with primary sources and everything. The long and short of it is that Japanese immigrants came to America, especially as the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) cut off the flow of cheap labor from China that had helped develop the Western United States by building railroads, working in mines, and the like. Japanese immigrants stepped in to fill that void, and Japanese communities sprouted not only on the West Coast but also in places like North Dakota and Arizona. Japanese communities flourished on the West Coast in the early 20th century – did you know that Portland’s Old Chinatown used to be Nihonmachi? American media, from popular novels to Hollywood, was littered with Japanese people, places, and things. There was even a Japanese leading man in the silent film era of Hollywood, Sessue Hayakawa. The tide began to turn in the 1920s, a reactionary time that saw the Ku Klux Klan experience a resurgence in popularity and the Johnson-Reed Act (1924) majorly restrict non-WASP immigration. Racism, eugenics, and nationalism were rampant. The Japanese communities that endured held on through the 1930s before they were uprooted and decimated by forced internment during the Second World War.

It took a while for Japanese culture to rebound in America. Part of this was anti-Japanese bias in the years after the war. Nevertheless, Japanese martial arts like karate and judo became popular. In the 1950s, Japanese cinema crossed over to American audiences in the forms of jidaigeki (period pieces set pre-Meiji) – like the samurai films of Akira Kurosawa, the themes of which resonated with Americans who had been fed a steady diet of Westerns – as well as kaiju (science fiction depicting giant monsters) like Godzilla. The 1960s saw some Japanese anime appear on American TV, like Astro Boy and Speed Racer. Did you know that a Japanese song – “Sukiyaki” by Kyu Sakamoto – topped the Billboard Hot 100 in 1963? The 60s also saw Japanese cuisine reemerging in popularity. The 70s and 80s brought martial arts films and video games. The Karate Kid, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and Power Rangers all have Japanese roots of varying degrees. Disney acquired the distribution rights for Studio Ghibli in America in 1996, and subsequent Oscar wins for Spirited Away (2003) and The Boy and the Heron (2024) underscored their critical and popular acclaim.

So clearly, Japanese culture in America was popular, even going back more than a century (though it ebbed and flowed). And yet, it feels like something has shifted more recently. As a kid, it felt like I grew up in a bubble when it came to Japanese culture because of my history (my mom doing JET, going to Japanese immersion elementary school… honestly, if you’re reading this, you probably already know my story). I remember being shocked upon learning that a kid my age (circa ten years old) didn’t know how to use chopsticks. Japanese culture in America felt niche, save for some phenomena in children’s media like Sanrio (as in Hello Kitty) or Pokemon. In the last five to ten years, it feels like all of a sudden, Japanese culture has exploded in popularity. In addition to anime/manga, food/drink and fashion have vaulted into the limelight. Now every college student is wearing Uniqlo and drinking hojicha. I am not sure of the explanation for this.

As I write this, I wonder how much of it is a vanity project, an avenue for me to complain that something I like has since become mainstream. Similar emotions were evoked when songs such as Roy Ayers Ubiquity’s “Everybody Loves the Sunshine” and Eazy-E’s “No More ?’s” became popular on TikTok. As someone who was essentially born into an affinity for Japan and began studying the language at a young age, I resent all these newcomers on my corner. If you would please consult the chart below (tongue-in-cheek, with a heavy dose of irony, etc).

There’s another piece to this as well, which is that some Westerners are really annoying about liking Japanese culture. They’re called weeaboos (or weebs for short), and they are obsessed with Japanese manga or anime. Now I generally try to operate under the premise that people should be allowed to enjoy things (editor’s note: this is a massive lie; the author thinks he’s cooler than everyone else because he watches Lynch and reads Pynchon, and derides popular media such as the Marvel Cinematic Universe as normie coworker slop). I understand that not everyone is into The Sopranos, dirty south hip-hop, and reading Wikipedia for pleasure. But weeaboos are so obsessive and immature about liking Japanese media that they draw the ire of those around them (although that might be a result of their perpetual state of unwash as well). This worship of Japanese culture is also sometimes accompanied by a fetishization of Japanese people (sexually/romantically) and society at large. If any weebs are reading this and are upset, please leave a comment below so we can have a respectful dialogue.

I felt the need to explain myself to people when I told them I was going to teach English in Japan, to clarify that I was not a weeb. Beyond Studio Ghibli (central to my childhood), a handful of food-centric Netflix shows (shoutout to Solitary Gourmet), and some 70s jazz-fusion (Masayoshi Takanaka and Jiro Inagaki), by and large, I am unfamiliar with Japanese media. Now that I am here, I’m trying to get put on to some Japanese movies, music, and television. If some people are so into it that it becomes their defining characteristic and annoys everyone in the general vicinity, then it must be pretty damn good. I’m starting my self-education with the novels of Haruki Murakami (having already completed A Wild Sheep Chase before my arrival) and the films of Akira Kurosawa (a sentence dripping with pretentiousness). And here is where we get into what I intended to discuss when I started typing this soliloquy.

You may not have heard of Kurosawa, one of the most important filmmakers of the 20th century, whose filmography includes Rashomon (1950), Ikiru (1952), Seven Samurai (1954), and Yojimbo (1961). He influenced and has been praised by many of our most notable filmmakers, including Spielberg, Polanski, Lumet, Kubrick, Altman, and Anderson (Wes, but probably Paul Thomas as well). I was tangentially aware (one of my favorite phrases as of late) of Kurosawa, but had not seen any of his work until now.

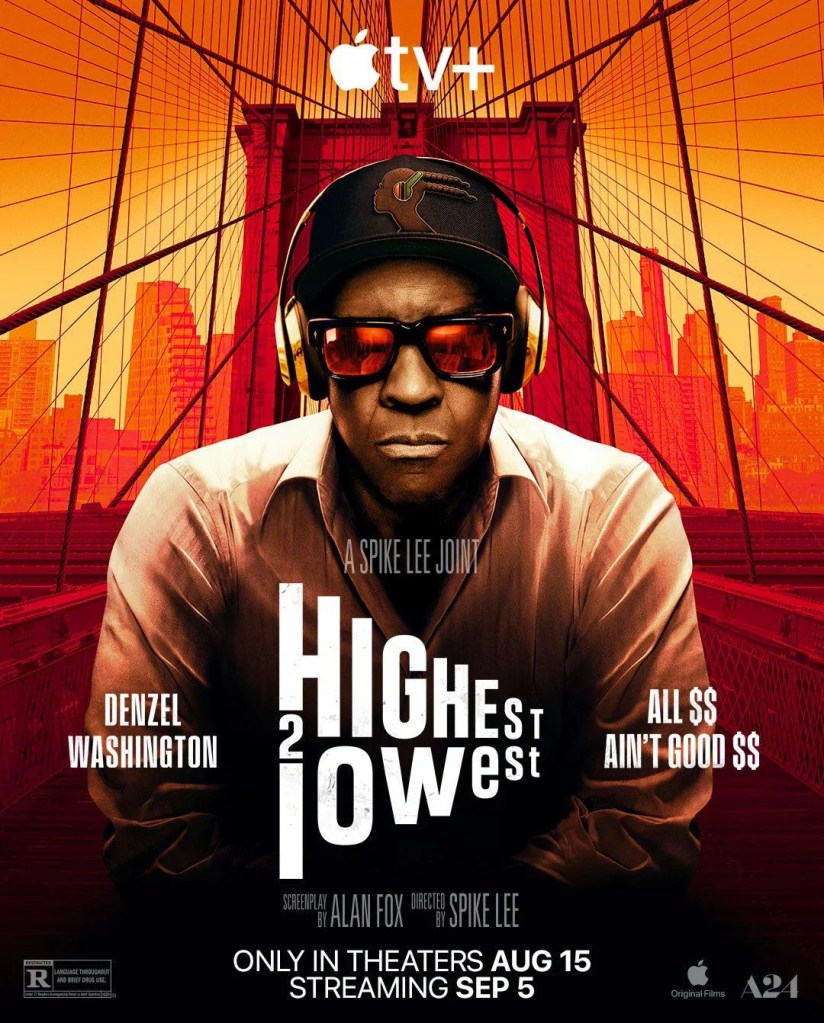

Earlier this summer, I was sitting in the movie theater with my parents, watching the trailers before Eddington (about which I could probably dash off another thousand words, but this post is already so long… let’s just say it was provocative). There were many upcoming movies that I wanted to see: Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another, an adaptation of Thomas Pynchon’s 1990 novel Vineland (which I am currently reading), and an A24 production of a UFC biopic starring Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson (equal parts genuine interest and morbid curiosity for that one), for instance. Somewhere in between those, I whispered to my parents that they should have the trailer for the new Spike Lee/Denzel Washington joint… and then I heard the opening notes of “The Payback” by James Brown. At this I leapt out of my seat, clapping and whistling uproariously before I was thoroughly shushed and someone nailed me in the back of the head with a 48 oz fountain soda (not true, but during the winter I did get hit in the back of the head by an empty beer cup while standing up in the nosebleeds at a Blazer game – in my defense it was during the closing seconds of a two-point loss).

Side note: Someone very smart once told me that I was “down on modernity.” I think with our current socio-political situation, it’s hard not to be down on modernity. With that said, this year has felt like a renaissance for both movies and music. Here’s my short list for new movies and albums that have restored my faith in the American artist as an institution. Not mentioned: Lil Wayne’s Tha Carter VI, which I didn’t even listen to all the way because it was so devastatingly abysmal. Such a shame, because Lil Wayne was arguably, as he claimed, the best rapper alive from around 1997-2010 (it’s probably between him and Jay-Z), although he was always a quantity-over-quality guy his peaks are among the highest ever in the genre (check out Tha Carter I, II, and III, as well a few of his many mixtapes like No Ceilings, Dedication 2, Da Drought 3, and Sorry 4 The Wait). Anyway, the list:

Music:

- Let God Sort Em Out: Clipse

- Live Laugh Love: Earl Sweatshirt

- Life is Beautiful: Larry June, 2 Chainz, and the Alchemist

- Alfredo 2: Freddie Gibbs, the Alchemist

- God Does Like Ugly: JID

- Victory: Slick Rick

- The Coldest Profession: DJ Premier, Roc Marciano

- Don’t Touch the Glass: Tyler, the Creator

- Lonely At The Top: Joey Bada$$

- Abi & Alan: Erykah Badu, the Alchemist (not yet released but eagerly anticipated)

- Multiple releases by Westside Gunn, Boldy James

Movies:

- The Phoenician Scheme: Wes Anderson, starring Benicio del Toro

- Eddington: Ari Aster, starring Joaquin Phoenix

- Sinners: Ryan Coogler, starring Michael B. Jordan

- Highest 2 Lowest: Spike Lee, starring Denzel Washington

- One Battle After Another: Paul Thomas Anderson, starring Leonardo DiCaprio (not yet released)

- The Smashing Machine: Benny Safdie, starring Dwayne Johnson (not yet released)

- Marty Supreme: Josh Safdie, starring Timothee Chalamet (not yet released)

Where was I? Oh yes. Spike and Denzel. One of the all-time director-actor pairings, who brought you Malcolm X (1992), He Got Game (1998), and Inside Man (2006). Their new film, Highest 2 Lowest, is a reinterpretation – not a remake, as Spike Lee recently stressed on the Bill Simmons Podcast – of Kurosawa’s High to Low (1963). As I watched the trailer in the theater back in Oregon, I couldn’t wait to see it in Japan. Only to arrive here and learn that the film would not be given a Japanese theatrical release – how absurd! When I was in Singapore and Stop Making Sense (1984) was re-released by A24 in theaters unavailable to me, I was upset, but I understood. Not releasing Highest 2 Lowest in Japan makes very little sense to me. So I had to wait until it was released on streaming (September 5th, on Apple TV). Usually, I am not a fan of when a movie gets released on streaming just a few weeks after its theatrical release, as I think it discourages people from going to the theater, but in this specific case, I am thankful.

First, my thoughts on High to Low. It’s a police procedural, and a basic plot overview without spoiling much follows (although it’s been out for 60+ years at this point, if you haven’t seen it by now, that’s on you). An executive at a shoe company (portrayed by Toshiro Mifune, the Denzel to Kurosawa’s Spike) struggles for control, and is in the midst of executing a scheme to buy out the other partners with his life savings to gain full control of the company, when a kidnapper mistakes his chauffeur’s son for his own, and kidnaps the boy for ransom. The kidnapping becomes a national sensation, and the police search for the kidnapper, eventually apprehending him.

There are major themes of class tension, especially in the extreme inequality of post-war Japan. I think when I was younger (even just a few years ago), I doubted how any movie in black and white could hold up to today’s standards. I no longer think that. High to Low is extremely impressive technically, in addition to the writing and acting. I don’t have the technical jargon of a film student, but the blocking, cinematography, and editing were excellent and, as I gather, extremely influential. And with regards to the black and white, the one use of color in the film made me audibly gasp.

Now I should say that I write this on August 29th, so I haven’t actually seen Highest 2 Lowest yet. I have tried my best to stay away from reviews, but apparently, they’re not glowing. Which is totally fine. Spike’s first movie, She’s Gotta Have It (1986) (also in black and white as a matter of fact) came out nearly 40 years ago; it’s okay if he is a little washed by now. To expect otherwise would be unrealistic. Not having seen it, I also think that the decision to cast A$AP Rocky as the kidnapper is a little stunt-y.

Okay, it’s now September 10th, and I just finished Highest 2 Lowest. I have a lot of thoughts. Let me start by saying that I wanted to really like this. But I think Spike kind of set himself up for failure because doing a reinterpretation of a highly acclaimed movie will inevitably be compared to the original. Remaking an old movie that wasn’t very good would be an easier task. The first part of the movie unfolds similarly to High to Low. Denzel is a record executive plotting a takeover of his label by buying out his partners to become the sole owner. While his son is at basketball camp along with the son of Denzel’s friend/chauffeur (portrayed by Jeffrey Wright), Wright’s character’s son is kidnapped in a case of mistaken identity, just as in High to Low.

Side note: the coach of the basketball camp is Rick Fox playing himself (Knicks, Bullets, and Blazers legend Rod Strickland appears briefly as the assistant coach), and when the police show up to question Fox, one of the officers asks Fox for an autograph. When Fox obliges, he asks the other cop, an Officer McGillicuddy, if he would like one as well. McGillicuddy declines, and his partner explains that it is because he is a Celtics fan. What I don’t get is that although Fox played seven years and won three championships with the Los Angeles Lakers, the eternal foe of the Celtics, he also played the first six years of his career for the Celtics! Shouldn’t a Celtics fan still want his autograph? While this was far from my biggest problem with the movie, it made no sense to me.

Anyway, back to the movie. Denzel pays the kidnapper the demanded ransom of $17.5 million by dropping it from the subway into the midst of the New York Puerto Rican parade (which looks like a great time). In exchange, the chauffeur’s son is returned. When questioned by the police in search of any leads, the recently returned son can recall hearing a rap song playing in the background while he was tied up. Denzel, while listening to a playlist of new music (as a record executive does to scout talent), recognizes the song from the chauffeur’s son’s description, and realizes that the voice he hears rapping is the same voice that demanded the ransom over the phone. With this clue, Denzel and Jeffrey Wright track down the kidnapper, portrayed by A$AP Rocky. Denzel finds him in the studio and confronts him; a chase scene ensues, and Denzel tracks him down on the subway and beats him up. That’s basically it.

Mifune and Denzel on their respective trains pondering the prospect of giving away their life savings for their chauffeur’s son

I had three main problems with Highest 2 Lowest. First, High to Low is primarily a police procedural. While the first third of the movie features Mifune (Kurosawa’s Denzel), the middle third is centered around the police trying to track down the kidnapper. In Highest 2 Lowest, Denzel does all of the police work himself (by happening to listen to the kidnapper’s song), and then tracks down the kidnapper himself. It’s more of a Denzel action movie from a script standpoint, but the action is confined to a chase sequence and a subway fight scene (in which Denzel looks his age, albeit a spry 70 years old – also A$AP Rocky is supposed to be a gangster, but he gets his ass kicked by someone twice his age). Not that I object to the portrayal of police as incompetent, but the movie felt very thin outside of Denzel, without any of his Equalizer-esque badassery. The cops are played by two actors who are more known for their work on the stage (as in they’ve been nominated for Tonys, not Oscars), and Dean Winters, who I primarily know from 30 Rock and Allstate commercials, but was also in Oz and SVU. While a better actor in a police role would have improved the movie, they also would have needed the script to carve out a larger role. To add insult to injury, Wendell Pierce, primarily known as Bunk from The Wire, appears in one scene as one of Denzel’s business associates (he is apparently having a big 2025, since I saw on Twitter that he was also in the new Superman). If you rewrote the script to make the police slightly more involved and cast Pierce, who gave arguably the greatest acting job as a detective ever, as the lead detective instead of some random guy, this movie is maybe 25% better.

Second, I must touch on the decision to cast A$AP Rocky as the kidnapper. Though we hear his voice over the phone, he doesn’t appear on screen until the last 30 minutes. When Denzel accosts him in the studio, they have a heart-to-heart in the form of a rap battle, where Rocky explains that he idolized Denzel’s character, tried to attract his attention in order to get signed to his label for years, and finally resorted to the kidnapping. This interaction ends with Rocky pulling a gun on Denzel, and then the chase and subway fight ensues. There’s another scene at the end that parallels High to Low, when Denzel meets Rocky in jail (after a bizarre music video-esque scene set in the courthouse). Rocky claims that the kidnapping has vaulted his music to viral status, and offers Denzel the coveted chance to sign him (even though Rocky has been sentenced to 25 years). Denzel explains that he is leaving his label to start a smaller family-run enterprise and declines Rocky’s offer, sending him into a rage. So in the entire movie, Rocky is basically in two scenes. I suppose he does a solid job – after all, it’s not easy to act alongside Denzel in what is essentially your debut. However, it felt like Spike Lee was trying to hide him by limiting his on-screen presence. I just find it hard to believe that Spike wrote the movie and then settled on A$AP Rocky after a lengthy casting process. It seems more like Spike specifically wanted A$AP for the role. Maybe to appeal to a younger audience (as rappers Ice Spice and Princess Nokia also make appearances), or maybe to promote the movie through original songs by Rocky. I can’t help but think that a better actor here – maybe LaKeith Stanfield – makes this role a little stronger. I guess this is similar to my first problem with the movie – whereas High to Low is really a group effort from the shoe executive, the police, and the kidnapper, Spike shaves down those supporting parts in favor of letting Denzel carry the movie. But much like Rod Strickland’s former teammate Kevin Garnett, a superstar carrying a mediocre supporting cast can only go so far.

Finally, I think some of the overarching themes that made High to Low so good were diluted in Highest 2 Lowest, a missed opportunity when there is plenty of fodder available. High to Low is a window into the social, political, and economic tensions in post-war Japan. The wealth of Mifune’s character, the shoe executive, is contrasted with the poverty of the kidnapper. One of the clues that eventually leads the police to the kidnapper is when he informs Mifune on the phone that he is looking up at Mifune’s hilltop mansion. This is paralleled in Highest 2 Lowest, as Denzel lives in a Dumbo penthouse, literally looking down on the rest of Brooklyn. And while we get dramatic scenes in High to Low that inform us of the kidnapper’s dire straits – including an incredible stretch where he scores heroin in a nightclub patronized by primarily American soldiers, and takes it back to a crack/flop house where a woman overdoses and dies – all we see of Rocky’s poverty is the brief scene where Jeffrey Wright’s son is tied up in a bathtub, Rocky’s small but well-maintained apartment in the projects where Denzel meets his wife and infant son (who is named after Denzel’s character), and the penultimate scene in the studio, which is in the sketchy basement of another apartment building. Although the movie tells us that Denzel’s character grew up in the same neighborhood that Rocky calls home, we see countless examples of Denzel’s wealth (from his Rolls-Royce to his wife’s Cartier bracelet) and not enough of Rocky’s poverty. Instead, the primary theme seems to be about how Denzel didn’t sell out by allowing his label to be sold to a conglomerate or by allowing the use of artificial intelligence in the music-making process. Rather, Denzel remained committed to his ideals by starting a smaller record label where he could be more involved in the curation of artists. While Kurosawa offers a stunning critique of capitalism and opulence, Spike chooses another message about authenticity that comes off lukewarm.

At the end of the day, Denzel is still arguably the greatest actor of the past half-century, and delivers a performance that while by his standards is maybe a B, 90% of actors could never reach those heights. Same goes for Spike. There are still some good moments in this movie. Watching Denzel drive around New York while listening to James Brown is familiar and comforting, like slipping into a warm bath. However, it’s a thriller that doesn’t thrill with a climactic action scene that feels clumsy. Outside of Denzel, the movie is very thin (although Wright is a great actor and gives a good performance). The larger point I’m trying to make here is not moot just because Spike’s movie was slightly mid.

What is the point I’m trying to make? That the cultural exchange process between Japan and America is more than 150 years old. It hasn’t always been conducted on equal terms. The United States forced Japan to open its ports to trade with the West. Decades before the United States refashioned a defeated fascist Japan into a Western-friendly capitalist trading partner, Japan sought to remake itself in the image of the West by emulating everything from their industrial strategy to their diet. Including playing baseball. Japanese culture enjoyed a brief popularity in America before being drowned in a tsunami of hate and bigotry. After the bomb, American soldiers lingered and left behind blue jeans and rock n’ roll. As Japan roses from the ashes, America consumed their electronics and cartoons. Sushi, video games, and martial arts followed. That pretty much brings us to the present, where hordes of American tourists descend upon Japan in ever-increasing numbers. I guess I don’t have an argument, but I do have a plea. Let’s understand our cultural counterparts as fully formed nations, with all the nuances and dark sides of any other place. Japan is not some mythical land of ninjas and Godzillas – real people live here.

Also can you guys pick a different country to be obsessed with? Or maybe it’s me who should change: “Japan’s played out, man… I’m headed to Mongolia…”

Japanese glossary:

- oyatoi: foreigners hired by the Japanese government to provide their expertise in respective fields and assist with the Meiji modernization process

- jidaigeki: period pieces set pre-Meiji

- kaiju: science fiction movies depicting giant monsters, like Godzilla

- hojicha: roasted green tea

Isn’t this supposed to be a food blog? I touched on history, culture, music, and movies, but failed to mention even a single thing I ate. I talked about Alfredo, but that’s not even food in this context. More food content coming soon, guys, don’t worry.

Leave a reply to Nora Cancel reply